The Third Act

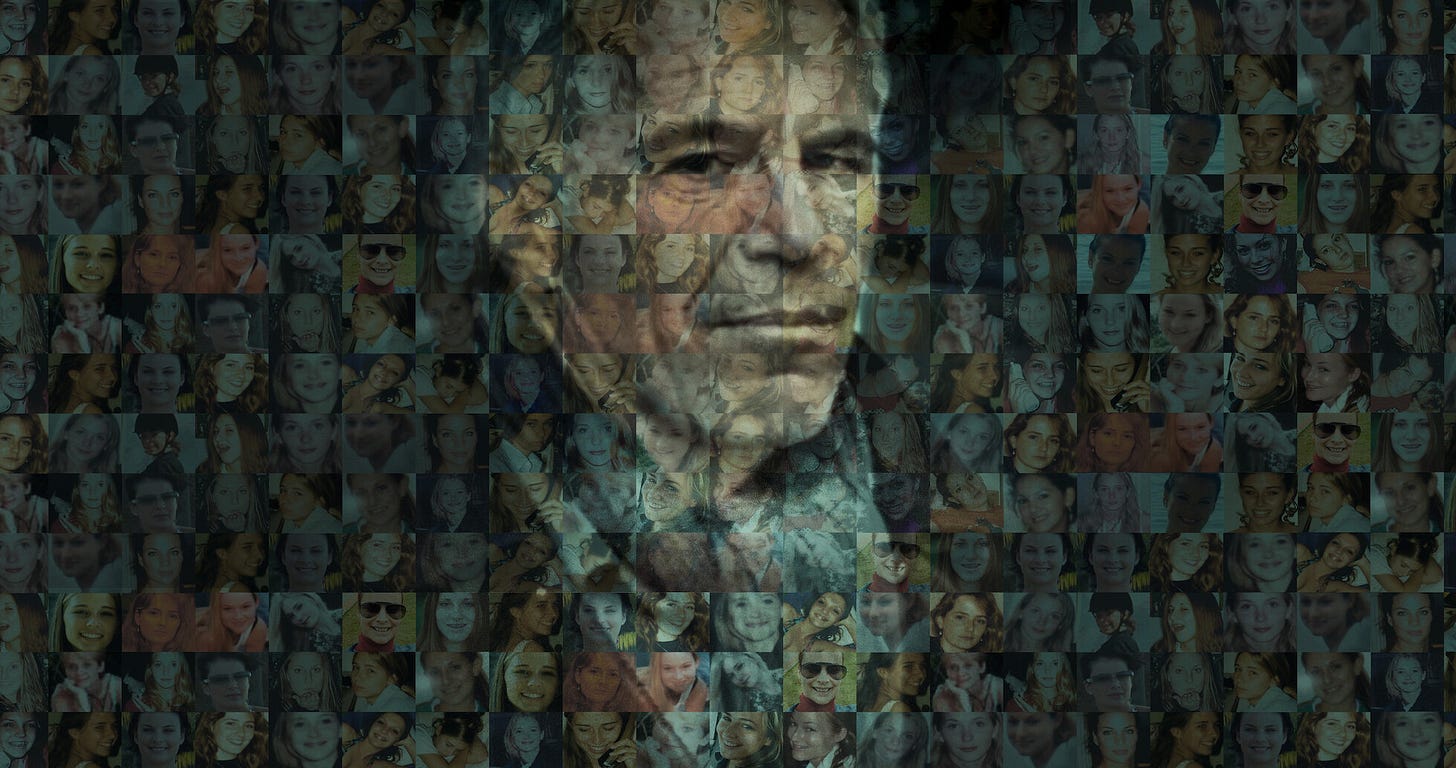

Jeffrey Epstein and the Prestige Economy

There is much to be said about the nightmare that is the case of Jeffrey Epstein. One is horrified by every detail that surfaces, equally horrified by the nearly successful political cover-up that surrounded it, and now increasingly horrified by the eruption of the online sewers, the antisemitic pathology, conspiracy enthusiasm of every stripe, feasting on the wreckage of so many lives. I have no wish to comment on any of this directly. It’s already bad enough. But two lessons press themselves upon me before I say the one thing I think actually deserves saying.

The first is really not new. Where there is money and power, there will be corruption, and much of it sexual. Liberal society may indulge its fictions of rational self-governance, but this is precisely why massive systems of deterrence and restraint — moral, religious, political, legal, etc. — must always be imposed, and even those will not always hold, least of all for the people who manage them. The second lesson is modern, a corollary of Murphy’s Law for the algorithmic age: anything that can become a spectacle will become one, instantly and totally. Engagement farming ensures that nothing, sacred or profane, high or low, personal or public, remains untouched. All will be consumed.

I have little else to say about the affair itself. It is all a nightmare. But there is one dimension of the public response I think warrants some reflection, because it touches something deeper than Epstein, or perhaps I can opportunistically use to muse on some ideas.

People are shocked at the sheer number of intelligent, learned, and prestigious figures who populated this man’s circles. A necessary point before I go further: not everyone associated with Epstein was necessarily a participant in his crimes. To claim otherwise is reckless and irresponsible, which is exactly what the engagement farmers are doing. The released files are still under investigation. But the shock itself is not misplaced. It is, in fact, one of the most instructive things about this entire episode, and the reason has everything to do with what kind of man Epstein actually was.

It has become abundantly clear from the available material that Epstein, aside from being a psychopathic sexual predator and pedophile, was a moron. Clearly, not in calculative and financial matters — he was obviously gifted at networking, at converting one asset into another, connections into money, money into influence, influence into protection. But intellectually, as a human presence, the man was nothing. He could not express himself with any clarity or eloquence. He had no ideas worth hearing. No compelling things to say. His recorded conversations were banality, platitudes, hearsay, rumors, half-digested cliches recycled without comprehension. His aesthetics and taste weren’t any better. He was neither interesting, nor learned, nor funny, nor pleasant in any discernible way.

And this, at least to me, is not a minor detail. It means that these brilliant men — professors, statesmen, scientists, public intellectuals, former and current presidents and prime ministers, Arabian princes — were not gathered around a brilliant man. They were not there for the conversation, because there was no conversation to be had. They were there for the network, the access, the proximity to money, and leverage. They were there, in a word, for the switching. Epstein was a switchboard, not a mind in any interesting sense, and the fact that all these extraordinary intellects orbited a switchboard tells you something about the actual structure of high society. The prestige economy does not run on excellence. It runs on connectivity — on the capacity to convert one form of capital into another. And every person who sat at Epstein’s table understood this, whether they admitted it to themselves or not. They were there because they needed switching done, and they were willing to sit across from a vacancy in order to get it.

But a second problem compounds the first and makes it far worse. Epstein was not merely stupid; he was entirely and openly committed to his sexually predatory life. This was clearly not some concealed compartment of his life but its ambient atmosphere, its visible animating principle. To encounter the man once or twice at a dinner is perfectly understandable. But to frequent his circles over extended periods and fly on his jets to his island — and here I will still assume complete innocence until one is proven guilty, assume that not one of these men partook in any of his criminal activities — you noticed nothing? You smelled nothing? Never once paused to wonder why there were always young girls around? Anything?

These men were so hungry for access that they made themselves willfully ignorant. And that is true enough. But I want to press harder on the nature of this blindness, because I do not think intelligence merely failed to prevent it. I think intelligence is what actively produced it. This is what intelligence does, and which people are in denial about. It does not illuminate; it rationalizes. The sharper the mind, the more sophisticated its capacity for self-deception, the more elaborate the architecture of justification it can erect around whatever it needs not to see. A dull man might have noticed something wrong simply because he lacked the cognitive machinery to explain it away. A brilliant man can construct, in real time, an entire interpretive framework, a colossal edifice of reasons, in which the young girls are assistants, the atmosphere is eccentric rather than predatory, and his own presence is innocent because his intentions are. Intelligence is not a light that reveals but often the very tool with which we furnish the darkness.

And there is something structural here too, and not merely psychological. To see clearly — to name the thing before you — is, often, to exit the game altogether. The man who asks sincerely, “Jeff… haaa..ummm….. why are there always young girls around?” is the man who loses his invitation. If one was not willing to participate in the crimes, then willful blindness is the minimum price of admission. The system does not accidentally produce people who cannot see. It selects for them. It rewards the narrow technical brilliance that can parse a genome or model a derivative while remaining magnificently incapable, or unwilling, of reading a room. We have built an entire civilization that systematically produces brilliant moral idiots — men whose intelligence is so specialized, so exquisitely refined, that it has atrophied entirely in every domain that matters for being human. And we have told these men, and they have believed it, and we have believed it about them, that their expertise is a form of wisdom. That their prestige means they are not what the rest of us are.

This is the deeper lesson, and it extends far beyond Epstein. The great deceit of liberal society — and perhaps of every civilization that has believed its own mythology — is the quiet, almost unconscious faith that intelligence makes one good. That talent is a species of salvation. That the accomplished and the credentialed have, by some unspoken alchemy, transcended the ordinary human condition. We do not say this outright, of course. But we live as though it were true. We build institutions on the assumption. We defer to expertise as though it were holiness. We treat the prestigious as though they have been, in some secular and almost sacramental sense, redeemed.

This is why I love the word prestige. It is, etymologically, a confession of exactly this deceit — hiding in plain sight in the very language we use to describe social distinction.

The word descends from the Latin praestigiae: tricks, deceptions, illusions. A praestigiator was a conjurer, a juggler, an impostor — one who cast a glamour over the eyes of his audience. When the word entered French, it retained this meaning: prestige referred to an enchantment, a spell, the power to deceive the senses. To speak of someone’s prestige in seventeenth-century French was really not to praise them; it was to warn that they had cast an illusion over you. Only gradually, across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, did the word undergo its extraordinary migration — from the vocabulary of trickery to the highest language of social admiration. The dazzlement remained, but the suspicion fell away entirely. We forgot what the word was telling us.

That a word meaning magicians’ trick could migrate, without anyone seeming to notice or object, into the supreme vocabulary of social distinction — this is itself the trick. The word has performed upon our culture the very trick it was supposed to name.

A novelist, Christopher Priest—and Nolan’s excellent film adaptation—once proposed a useful anatomy of the magician’s art. Every magic act is composed of three movements. The first is the pledge: the magician takes something ordinary — his hat, a coin, a stick — and shows it to the audience, making sure they see its ordinariness. The second is the turn: he takes that ordinary thing and does something extraordinary with it, makes it vanish. But this, contrary to what one might expect, is still not truly impressive. Making something disappear is clever, but no one in the audience actually believes it is magic. The real work — the moment the magician becomes a magician, the moment belief is fully induced — occurs only in the third movement, the prestige: the vanished object is restored, produced from behind your ear, retrieved from impossibility. Then comes the gasp. The wide eyes. The delighted surrender to the conviction that this person before you is truly extraordinary, that he is not what he was, that something has genuinely been transcended.

Prestige is, thus, counterfeit resurrection. The ordinary thing disappears; the extraordinary thing appears in its place; the audience believes a transformation has occurred. And this is precisely what social prestige performs upon the person. It takes the ordinary, fallen, mortal creature — the same creature who is proud, lustful, cowardly, self-deceived — and produces, as if from nowhere, the figure of the Great Man, the Distinguished Professor, the Visionary Statesman, someone who appears to have transcended the common human condition. It is a secular soteriology. The gospel of modernity: you shall be saved by your brilliance. You shall be redeemed by success. And the audience gasps, and believes, and defers — because the prestige is performed so well that everyone forgets it is the third act of a trick.

But the magician knows. He always knows. Nothing actually disappeared, and nothing actually returned. The ordinary man is still there behind the extraordinary reputation, unchanged, unredeemed, as susceptible to corruption and blindness and moral stupidity as anyone who never won a prize or held a chair. Epstein’s circles have, perhaps more vividly than anything else in recent memory, let us see backstage. The pledge, the turn, the prestige — all suddenly visible as what they always were: deception.

Let this much, then, be clear. To say prestige is an illusion is not to say that brilliance is not real, or that talent does not exist, or that these men do not genuinely excel in their fields. They may well. But none of it — none of it — means they are anything more than what we all are: fallen, mortal, proud, blind, and delusional creatures who require restraints we did not design and cannot reliably impose upon ourselves.

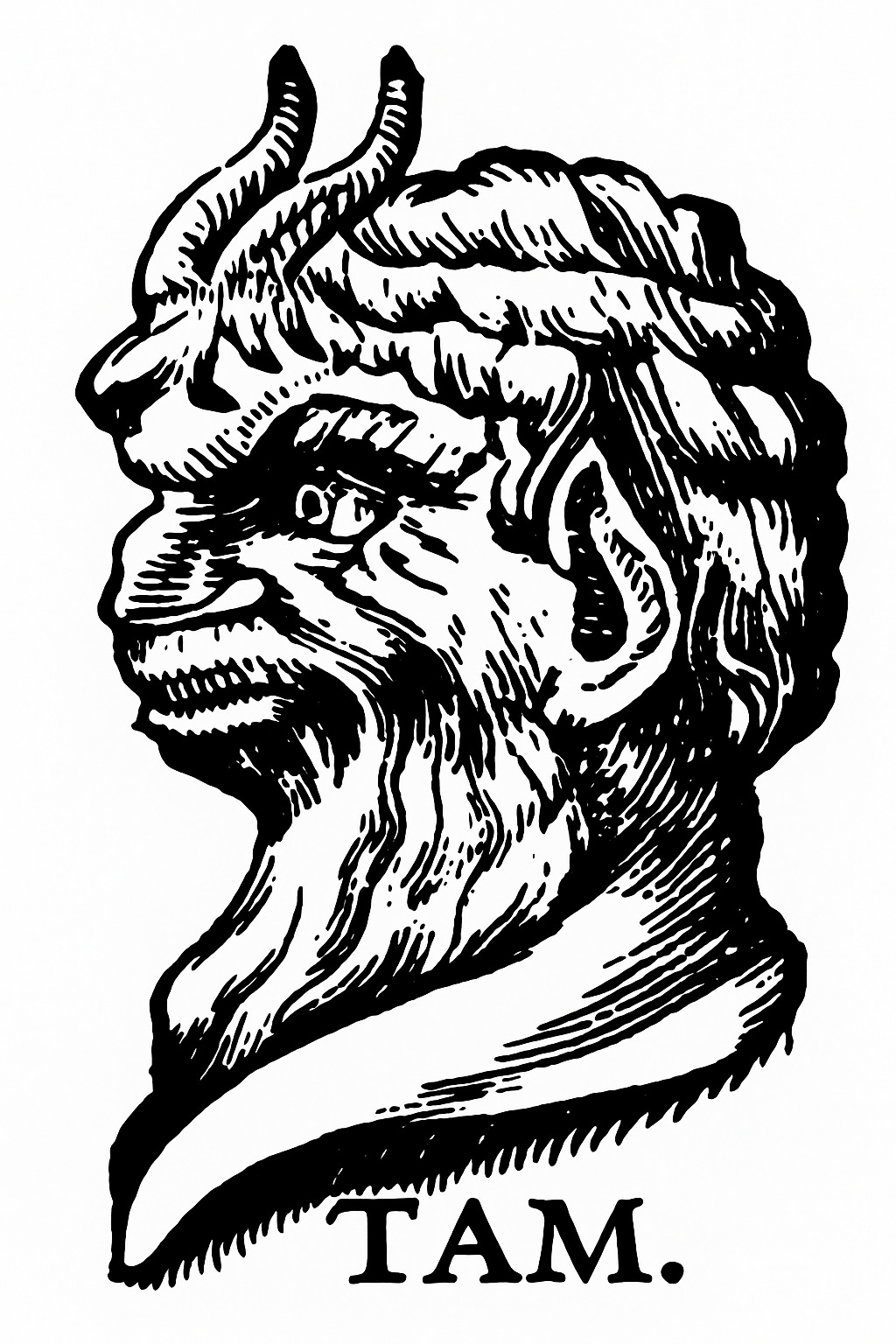

It is fitting, perhaps, that the most honest voice in all of Western literature on this subject belongs to the devil. Goethe gives the line to Mephistopheles, who would know:

Du bist am Ende — was du bist. Setz dir Perücken auf von Millionen Locken, Setz deinen Fuß auf ellenhohe Socken, Du bleibst doch immer, was du bist.

You are, in the end, what you are. Put on wigs of a million curls, stand upon the highest stilts — you remain, forever, what you are.

Hussein Aboubakr Mansour is wise beyond his years and understand us so well.

This is an excellent article, of course (we expect, and receive, nothing less). But I would add one other underlying problem: the liberal dream of restricting inequality to meritocracy. In reality, as compared to any of the utopian fever dreams that plague our world, communities always have elites that are there because they are there -- inherited the job, rose up on some sort of merit, or knew the right people. The pretence -- that complex societies do not need a network of elite people (some of whom will be fools and/or slime, because "knowing the right people" is a task that is largely, although not always, done by ambitious fools or crafty slime) -- is dangerous.

It is certainly dangerous for the moral character of the elite. They almost always operate behind a cloak of invisibility -- all good liberals know that there is no communicating elite, only a meritocracy, so these good liberals cannot see something that they do not think could exist in the liberal society. As Plato suggests, invisibility invites bad behaviour. The Epstein tell is an exception, but the concept of an elite that is nothing special (other than talents that are mostly irrelevant to the current functions of the people involved) is so alien to the liberal imagination that I would be astounded if there are more than a few token cancellations or prosecutions before life goes back to normal. As you say, the power of rationalisation is strong among them...

For the world, probably not so much. Our elites are no worse than any elite would be when it is not constrained by some sort of shame in the face of God or some other sacred thing (honour, the fatherland, the spirits). And I would argue that our elites are pretty competent at the things we really care about, which is certainly not high ethical standards. The world is prosperous, much of it is peaceful, and we keep getting new technologies. What more could a modern person ask from the elite?

If we accepted that we do need an elite that is not meritocratic, we might try hard to impose ethical standards on them. But such acceptance is not going to come easily, and not because of a wicked conspiracy. To impose ethical standards you have to have standards that are perceived as universal and that are never lower than aspirational. Both of those conditions are so far from the current social imaginary that no scandal, no matter how repellent or widespread, is likely to have much effect.