"He is our neighbor, the best we could ever ask for.

At dusk, he sits on the bench, enrobed with his gown.

His presence perfects the majesty of the street and the beauty of the trees. And when the last ray of light disappears from the skies, his three sons return from their labor.

On the eve of their coming pilgrimage, he looked into their faces and asked:

- What are your thoughts on the occurrences that have unfolded?

The eldest son responded:

- There is no hope without law.

The middle son:

- There is no life without love.

The youngest responded:

- Absent justice, there exists neither law nor love.

The patriarch smiled and said:

- There must be a measure of disorder so that the slumbering might be awakened.

The three brothers exchanged looks and then said in one voice:

- Truth is always what you say." —The Dialogue of the Dusk

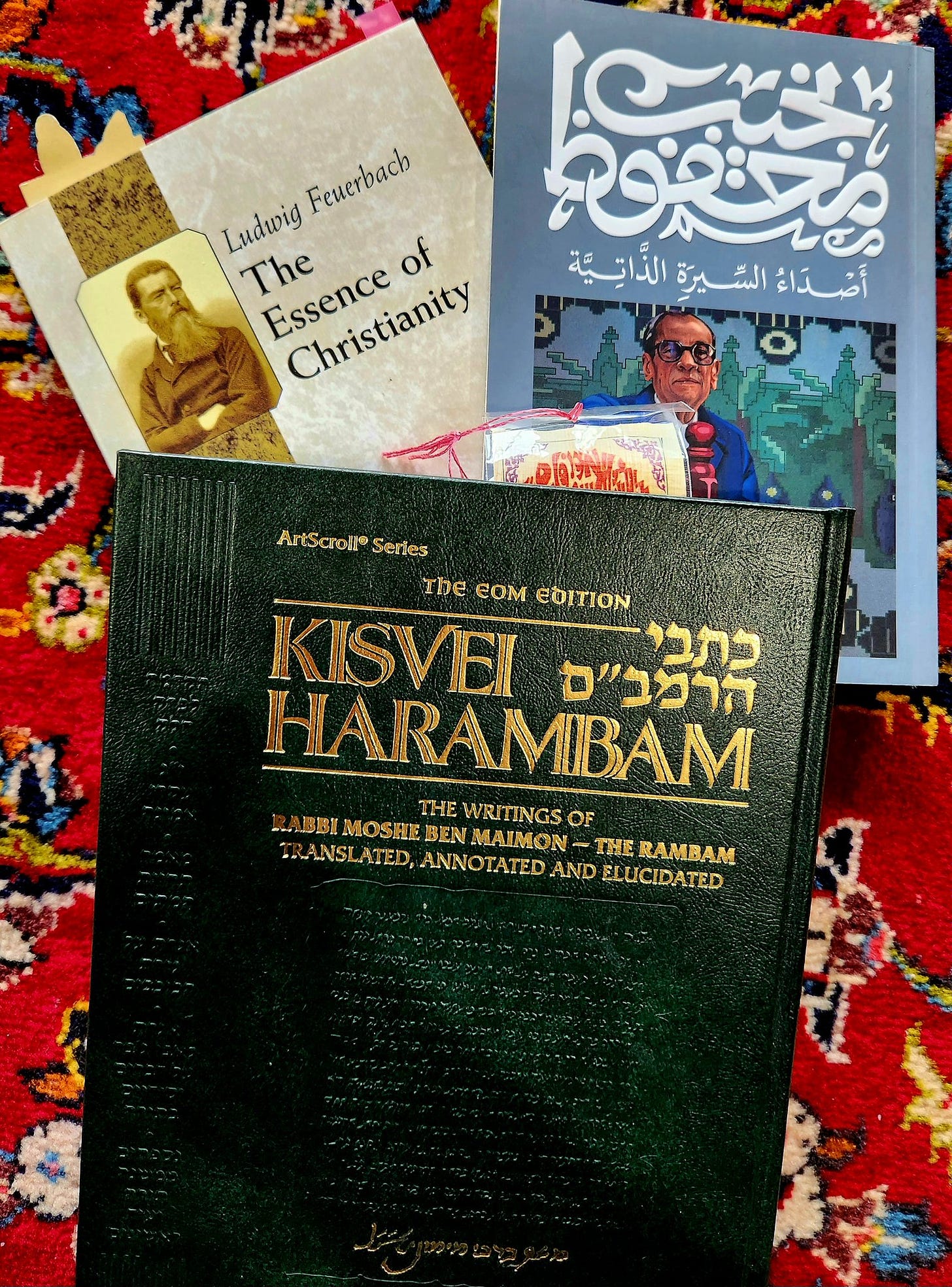

Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz published this allegorical short story in his 1996's Echoes of an Autobiography. This was only one year when Mahfouz had survived an assassination attempt by Islamic attempt by Islamic fundamentalists just outside of his home in Cairo. The then 86-year-old author was stabbed multiple times but thankfully survived with minimal lasting complications. His Echoes, a collection of short stories, allegories, and aphorisms, entirely revolves around the questions of God, revolution, life, and death, and that was the culmination of a lifelong meditation on these questions, a mediation started in the 1960s and which consumed all Mahfouz's works since then. It is the tragedy of the Muslim Arab world, a world that is yet to know itself, that the only figure with the most genuine, non-atheistic interest in faith and God in the Arab cultural establishment be targeted for being a propagator of "atheism."

In the allegory of the father and sons, Mahfouz examines, one last time, the three major religions of the Middle East: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and their relations to each other and to the questions they seek to answer. Mahfouz's first literary exploration of the conflicted Abrahamic world was in his famous Children of Our Alley, a much longer allegory in which the three religions appear as consecutive revolutions in the same neighborhood. Yet, the book was written in 1956 during the heyday of national liberation and Third World Marxism, and the revolutionary theme was an imprint of the time. As a matter of fact, the book ended with the emergence of the fourth revolution, Scientism, which sought to be the revolution to end all such revolutions.

But even at such an early stage of his life, in Children, Mahfouz was still uncertain about whether the fourth revolution of the man of new knowledge was really going to do what it sought. The book ends with a fear and a hope. Forty years later, in the allegory of the father and the three sons, the fourth son disappears altogether. He was nothing but a passing illusion, and we are left with the three old brothers. They returned to their father after a long day of labor and toil only to be asked about what they thought of the world in which they toiled. The three different answers exhibit the central ethos of the three religions, at least as Mahfouz sees them, constituting a single prolonged discourse. That is, mature Mahfouz, a man at the end of his life, did not see the three religions as competing gangs, as he did earlier in Children, but as a long dialogue between Man and God in which their three different answers form one long polemic against mankind. For the eldest, no hope, no straight thing could come out of the crooked temper of man but through law. For the second, only through charity (in the Christian sense). And the third insists on justice before either could even be possible.

Indeed, the three brothers give different answers, yet their answers are a thread of their collective dialogue with their father. One might have been waiting for the father's response. Who's right? Or maybe we are all wrong? But the father says nothing about the matter. He abruptly leaves the matter as if he wasn't the one who started the conversation. The sons are subject to his caprice and his arbitrary will. He then throws chaos and disorder at them, to which the three respond in a single voice and complete harmony: you are always right. Even as they are passionate about their answers, even as they are met with chaos, they ultimately agree to submit and surrender any claim to truth, to knowledge, or to justice and all their egoisms to him. Even as they speak, they know they possess nothing. Their final response was the renunciation of themselves in front of him, who possesses all truth and, in doing so, reaffirming themselves as a polemic against the human world of which they are a part.

A single prolonged polemic against man's egoism is how Mahfouz saw the three religions at the end of his life. Judaism was the first, polemicizing against man's sensuous egoism that made him into a beastly creature, redeeming him with order and law. Christianity was a polemic against man's tyrannical egoism, turning the redeeming law into control and tyranny. Islam was a polemic against man's unevenness, turning both former polemics into tools of egoist unfairness. Then, of course, the third son goes to reproduce all of the above.

This view of the three Abrahamic religions as primarily polemics against egoisms couldn't be more opposed to the analysis of religion established by German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, which came to be the critical basis of Marxism and of much modern atheistic humanism. For Feuerbach, religion (he primarily examined Christianity and Judaism) was nothing but distorted human egoism: man does not worship God; he worships himself concealed by a figment of his own imagination. Man first unconsciously and involuntarily creates God in his own image, endowing that created image with all his secret desires, egoism, and selfishness, and after this, God consciously and voluntarily creates man in his own image, returning such desires to Man.

Accordingly, Feuerbach saw the image of the Christian God, the unconditionally loving God, as nothing but the projection of man's need for love. The universalism of such God is nothing but the yearning for our own universalism. And unlike Christianity, which is an expression of universal religion, the national character of Judaism means that Jewish stories are projections of not universal but particularly Jewish characteristics. Feuerbach concluded,

"Jehovah is Israel's consciousness of the sacredness and necessity of his own existence—a necessity before which the existence of Nature, the existence of other nations…everything that stands in the way must be sacrificed; Jehovah is exclusive, monarchical arrogance, the annihilating flesh of anger… in a word, Jehovah is the ego of Israel, which regards itself as the end and aim…The doctrine of the Creation in its characteristic significance arises only on that stand-point where Man in practice makes nature merely the servant of his will and needs, and hence in thought also degrades it to a mere machine, a product of the will."

Judaism is "practical egoism" that looks at the world, at nature, from a practical standpoint, one of dominion and instrumentalization in which "nature is regarded only as an object of arbitrariness, of egoism, which uses nature only as an instrument of its own will and pleasure." The Greeks looked at nature and "heard heavenly music in the harmonious course of the stars… the Israelites, on the contrary, opened to nature only the gastric sense; their taste for nature lay only in the palate; their consciousness of God in eating manna." This theoretical outlook resulted in the brightest minds of pagan Greeks seeking philosophy and art. In contrast, the brightest minds of the Jews occupied themselves with dietary laws about bread and meat. "Eating is the most solemn act or the initiation of the Jewish religion." Jewish spirituality is a mere appetite for food.

Mahfouz's view of Abrahamic religions as a polemic against man's egoism and Feuerbach's view of them as the sharpest expression of such egoism and selfishness are such contrasts from one another that one should wonder were both genius men talking of the same thing. For Mahfouz, Judaism was man's desperation for hope in order; for Feuerbach, it was man's endless appetite for food. The true God of the Jews is not the mysterious father that possesses all truth but the sensuous appetite for endless selfish gastric consumption. Which is it?

I would argue that both are right. Mahfouz's words were those of an old man tested, fooled, tricked, promised, and disappointed both by himself and by time. These were the words of a man who finally saw the vanity of it all. Feuerbach's criticism of religion was that of the most primitive understanding, the most primitive state of egoist humanity, from which the religious world must start. It is the religion of human childhood. What Feuerbach and the modern university have done is take such a primitive understanding of religion, standardizing, absolutizing it, finalizing it, eternalizing it, and universalizing it, producing a world of highly educated atheistic humanistic men and women who are reproducing man's egoist and primitive understanding of religion. To understand this, we must then turn to Maimonides.

In his introduction to Perek Helek, the part on eternal life, in his Mishnah Commentary, Maimonides starts with some criticism of scholars and simple commoners whom he considered to be missing the entire point of the teachings and focusing on the trivial matters of the details of rewards and next life. They spend hours and days talking about the details of the heavenly delights they will enjoy, the exotic foods they will consume, and the wonders they will see. Feuerbach would have smirked approvingly. Rambam's tone is quite sharp and reveals a deep sense of frustration. In a certain part, he even begs the reader, who is holding too tight to superstition and confusion, to stop reading if they do not wish to be angered by what they are about to read next.

To correct these delusions, shared by the learned sage and the simple man alike, Rambam starts with a parable of his own of a Torah teacher who receives a child to become his student. As a child, the student can not understand what the Torah is or why it should be studied; thus, the teacher promises him candy and fruits if he does study it. And so, the child studies the Torah indeed for the sake of Feuerbach's "gastric pleasure." When the boy is older, the teacher must give him something more sophisticated, so he promises him clothes. In a later stage, money. In the latter stage, the study is rewarded with honor, prestige, and a job as a judge, which are respected and revered by the town. At a later stage, perhaps as the child reaches his 70th year, the child is promised more social honor as a learned pious sage, etc.

After Rambam offered us this parable within a parable, a parable with which to decode, or rather remystify, the parable of Eden and otherworldly delights, he then continued to amass a long list of rabbinical condemnations and strictures against those who learn Torah for anything but its own sake. The very purpose of living the law is living the law. The very reward of fulfilling the commandments is fulfilling the commandments. Seeking any other rewards is a form of despicable egoism that is neither holy nor pious, yet selfish and sinful. The very method of the parable is irredeemably condemned.

Here, Rambam faces us with a contradiction that he does not resolve. He starts by embracing the religious promise of earthly rewards and sensuous pleasures, Feuerbach’s gastric delights, yet ends with an unequivocal condemnation of such behavior, positing the purpose in God himself. Which is it? Is religion the gratification of human egoism, in the manner of Feuerbach, or a polemic against egoism, in the manner of Mahfouz?

Rambam's argument could be described as somewhat Hegelian (as much as I hate saying it). That is, religion must start, and there is no possibility for it to start without incorporating the very error that it seeks to correct. The religious polemic against man's egoism must start by incorporating the very egoism it seeks to cure. The child's journey to learn Torah just for its own sake is for the child to learn Torah for the sake of a piece of fig or sugar. Religion did not invent egoism, yet in order to cure it, it must adopt it. It is then up to man to climb the steep hill of religion out of the pit of his own narcissism. Rambam started with Feuerbach and ended with Mahfouz.

Yet, man is not guaranteed automatic progress in this line, and religion, most of the time and throughout history, has failed to overcome the egoism that it had to incorporate, becoming a tool of a more severe form of egoism. This is largely the situation today between the three religions, especially after secularism (which I support with qualifications and limitations) has brutalized the minds of men and women with the worst kinds of Feuerbachean primitivity. For many of our modern atheistic Muslims, Islam became nothing but the claim for chauvinism and supremacy; for the modern atheistic Christians, Christianity was the genius of a narcissistic, eternally beautiful Western civilization that is superior to all humanity, and for the contemporary atheistic Jew, Judaism is an ethnic superior intelligence and a cosmic quota of Nobel prizes. The new child doesn't just require candy in exchange for learning religion; he requires everything while refusing to learn anything at all.

This, of course, is only a reproduction of what has always been, as it's clear from Rambam's words, latent in traditional religion: man's egoism. Can we move on from Feuerbach to Mahfouz today? Is there any possibility for us to rediscover the truth that is incorporated in the error that we now made absolute? Can we, and I'm talking here of those with affiliation to the Abrahamic world, reread our warring egoisms as Mahfouz did as a single prolonged polemic against us, all of us? Is there a chance for men of faith to see their stories as part of a larger one which, while we can not grasp, we still trust against ourselves? Can we resist our own people and insist that our own religion, whatever that may be, is, first and foremost, a polemic against us and not a tool to feel superior to others? Can we do so without abandoning our particular answers yet while relinquishing any egoistic claim to truth to God only? Or are we doomed to be children insisting on figs and candies forever?

Of course, for most people, the main obstacle to doing so, of being Mahfouz, of reading the long dialogue, is nothing but our own egoism. The Jew doesn't believe the Christian nor the Muslim have anything to show him, not the least about himself. The Christian feels the same about both, the Muslim feels entitled to dominate both, and the three of them refuse to consider why Feuerbach came to see the three of them so revolting.

This is a good reading of Maimonides. And just a generally good essay. Thank you

Hussein, this was a pleasure to read. Its been a long time since I read something this spiritually enlightening. It's people like you who help us see the Mahfouzian potential in other faiths.